Sedation

290 - Conscious Sedation Training Versus Practice Amongst Recent Pediatric Dental Graduates

Elina Prakash, DMD

Postdoctoral Resident

New York University

New York, NY, New York, United States

Ronald W. Kosinski, DMD (he/him/his)

Clinical Director Oral Health Center for People with Disabilities

NYU

NYU College of Dentistry

New York, NY, New York, United States- LF

Lauren M. Feldman, DMD, MPH

Postdoctoral Program Director

NYU College of Dentistry, Pediatric Dental Department

New York, New York, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Research Mentor(s)

Program Director(s)

Purpose: This cross-sectional survey analyzes the relationship between post-doctoral oral conscious sedation training and current practices of pediatric dentists nationally. The survey also analyzes confidence in techniques as well as identifying trends in sedation.

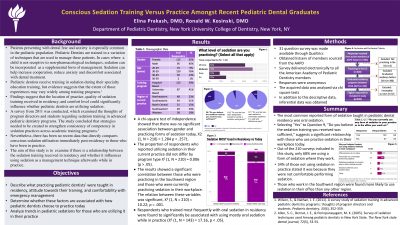

Methods: A 31 question survey comparing sedation training and current practices was made available through Qualtrics and delivered electronically to all the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry members through a listserv sourced from the AAPD.

Results: The most common form of sedation taught in pediatric dental residency programs was oral sedation. Of all the survey respondents who are practicing pediatric dentistry in the U.S. and who have graduated from a residency program in the last 10 years (2014-2023), only 68% are using a form of sedation where they work. The proportion of respondents who did report using sedation in their current practice had no relation to whether training done at a university or hospital-based program, X2 (1, N = 210) = 0.006 (p > .05). A significant association was found between respondents who stated to have trained most frequently with oral sedatives in residency and using mostly oral form of sedation while out in practice (X2 (1, N = 143) = 17.16, p < .05). The results also showed a significant correlation between those who are now practicing in the Southwest region and with those who are in fact utilizing some form of sedation in their workplace after residency. Respondents who responded “Yes” to Question 9, “Do you believe the sedation training you received was sufficient,” showed a significant correlation with those currently practicing sedation in their workplace practice (X2 (1, N = 210) = 5.40, p=.02, p < .05)

Conclusions: The data revealed that 34% of respondents opt out of using sedation in their workplace post-residency, citing the primary reason for refraining due to personal discomfort (37%). Among the 143 respondents who regularly practice sedation, a moderate level of oral conscious sedation was most commonly reported (75%), while deep sedation was the least preferred option (18%). The data from Figure 2 shows that the vast majority of subjects reported receiving training to manage sedation emergencies (Question 10) and felt confident in their ability to administer sedatives safely and effectively (Question 11). Despite the training reported, the analysis reveals that simply undergoing sedation training during residency doesn't always translate to active sedation practice in the workplace. This suggests a discrepancy between training received and its application in professional settings. Interestingly, respondents who believed that the sedation training they received during residency was sufficient (Question 9) showed a significant correlation with those currently practicing sedation in their workplace. Perceived confidence in administering sedatives safely speaks directly to an individual's self-assessment of their capabilities, whereas the adequacy of sedation training focuses on their assessment of the training program they underwent during residency. This implies that perceived adequacy of training may play a crucial role in motivating individuals to engage in sedation practice post-residency.

Overall, these findings highlight the complex relationship between sedation training, perceived adequacy of training, and actual sedation practice in the workplace.

.jpg)